Experts’Insights : Considerations Surrounding Social InnovationStrengths and Living Practices Needed to Deliver Social InnovationSocial, Corporate, and Personal Futures Explored through Aspiration and Independence

What it Takes for the Social Innovation Business to Anticipate Global Trends

The origins of Hitachi lie in the philosophy of contributing to society to which it has held since it was first established, as expressed by its mission of “contributing to society though the development of superior, original technology and products.” Its current Social Innovation Business can be thought of, then, as redefining this in terms of its own business domains. Rather than shareholder capitalism and financial capitalism with their pursuit of profit maximization, the Social Innovation Business is also aligned with the shifts in society over recent years that have refocused attention on the resolution of societal challenges, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), Society 5.0, and investment based on environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) considerations.

The real beginnings of the Social Innovation Business can be found in the shadow of the global financial crisis of 2007–08. While the concept was not well understood in the early days, a large number of people have since come to recognize its potential, giving a visceral sense of how the business has anticipated societal trends at a global level.

One word that has risen in prominence internationally with this wider action on societal challenges is “purpose.” It translates to Japanese terms for goals and for understanding of what it is you are here to do. As well as being a key word in the international business trend toward transcending shareholder capitalism, it is also a concept of great significance to the social entrepreneurs of the millennial generation. Reflecting on the past’s purposeless pursuit of gain, placing an emphasis on goals and a sense of purpose is coming to be seen also as the key to sustainable growth in corporate activity.

The training given to those selected for the Hitachi Academy seeks to emphasize “purpose-driven leadership,” where by “purpose” I particularly mean the Japanese term “kokorozashi” (aspiration or will). I also tend to think of this as corresponding to the intersection between what society needs, what actions the company ought to take, and what the individual wants to do. It is this “true kokorozashi” that provides the strength to endure difficulties and overcome challenges. In fact, the word “purpose” also embodies a determination to overcome.

There was a sense, predating even the arrival of COVID-19, that a deep unease with the rapid pace of social change had been spreading more widely among people, including in relation to advances in technology such as artificial intelligence (AI) and the negative impacts of excessive shareholder capitalism and globalization. The shift toward an emphasis on purpose in business is a new sign highlighting the strength of people’s autonomy and volition in this time of uncertainty when the future is unclear. It can also be said to be aligned with the thinking behind the Social Innovation Business inspired by a desire to contribute to society.

Meanwhile, it goes without saying that companies also need to pursue profit if they are to continue contributing to society. In its 2021 Mid-term Management Plan, Hitachi announced its intention to simultaneously enhance social, environmental, and economic value, and in doing so the company is first of all bringing innovation to society in the form of businesses that are sustainable and have a greater impact. Herein lies the significance of Hitachi, a business rather than a non-political organization (NPO), showing leadership in social innovation.

Achieving DX through Combination of Domain Knowledge and Digital Technology

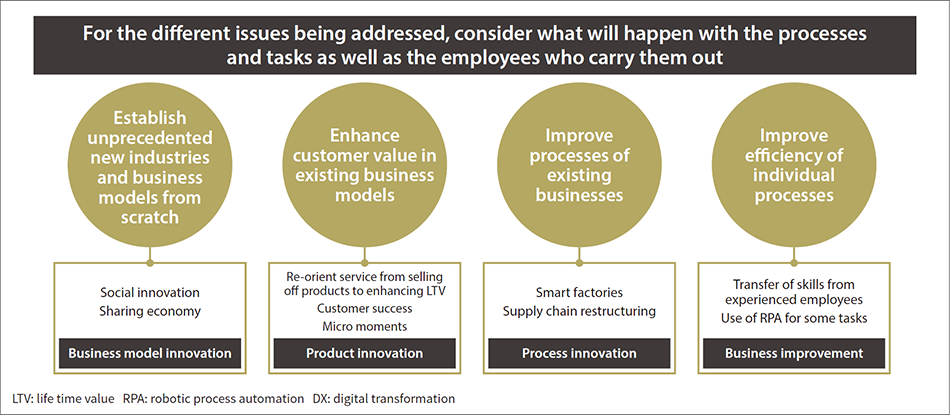

Something else that cannot be overlooked when talking about societal trends is digital transformation (DX). While the tendency is to use the term DX as if it were synonymous with the adoption of IT or digitalization, genuine DX is a broader concept that relates to the use of digital technology to change business and the very structure of industries. Given the current environment where digital technology underpins the various different foundations of society, it will not be possible to realize the potential of future society without it. Treating it as a means of pursuing its Social Innovation Business, Hitachi Academy addresses DX in terms of four different perspectives, namely business models, products, processes, and operational reform.

What this highlights is that, along with the generally recognized need for AI experts, data scientists, and other specialists to be involved in achieving DX, people who can define the issues also have an important role to play. Defining issues requires extensive business expertise and domain knowledge, and it is here where Hitachi’s strength lies. Hitachi has the capabilities needed to use technologies like AI to analyze and integrate large quantities of data acquired from equipment operating at diverse plants and other such sites, and to use the results to provide real-time feedback. Hitachi’s mission for the future is to build cyber-physical systems (CPSs) like these to enable digital technology to be put to use resolving real-world problems. This is a capability that fast-moving IT venture businesses find difficult to replicate.

Along with training data scientists and other DX experts this year, Hitachi has also launched a group-wide digital literacy exercise program for employees in order to raise the standard of digital competence. The aim is to equip employees with the grounding they need to make their own judgements on what digital technology and DX are capable of, and whether digital technology can provide solutions to the challenges currently facing customers. While working alongside leading-edge IT divisions, the company will go about DX in a way that makes the most of the strength Hitachi possesses in terms of knowledge from both the real-world and digital realms.

Achieving Internationally Standardized Human Capital Management

If Hitachi is to operate its Social Innovation Business globally, it is also essential that its human capital management practices conform to international standards. Hitachi recognized this need from an early stage and launched reforms to this end in 2011, just as our Social Innovation Business was getting underway in earnest.

Whereas it is possible for Japanese practices to be successfully transplanted into overseas production facilities or sales companies in the case of export industries, the situation with the Social Innovation Business is entirely different. Here, the Social Innovation Business needs leaders familiar with local areas and markets, and as many “global” leaders who can coordinate activities across all worldwide operations as the number of markets and businesses involved. Achieving this calls for the unification of group systems and databases to ensure the ready availability of human capital information and the full use of human capital. Moreover, the global standardization of core systems is of immeasurable value given the impossibility of coordinating the management of a wide variety of personnel spread around the world when there are around a thousand different management systems in use by the various local subsidiaries and group companies for whom they work.

Rather than adopting existing Japanese practices, the human capital management reforms that this inspired were undertaken, from the very beginning, on the basis of designing systems based on international standards that could be used globally. The outcome of all this work, spanning close to a decade, was Hitachi’s job-based human capital management. Many readers may already be familiar with this from the public attention it has garnered in relation to telework as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Job-based Employment as a Means of Living an Independent Life

Job-based employment arrangements have long been a standard practice in Asia as well as in Europe and America. In contrast, Japan’s membership approach is an outlier, a system that arose out of the conditions that applied during the nation’s period of rapid economic growth. As such, it does not work in other countries. As the membership approach that is emblematic of Japanese management carries a strong image of safety and security based on group consciousness, a shift to job-based employment frequently provokes resistance or is viewed with apprehension. I believe, however, that this is mainly due to basic misapprehensions and misplaced assumptions caused by a lack of understanding of the true nature of job-based employment and how it works in practice.

A job-based approach is not incompatible with long-term employment and suits both new graduates and long-serving employees. The problem, as exemplified by the notion of a company-based career, is that lifetime employment and the bulk recruitment of new graduates causes organizations to turn inward, causing them to atrophy and lose dynamism. It seems to me that, if they are to maintain vibrancy and vigor, companies and workplaces should aspire to a diverse mix of personnel as suits their management environment and business, regardless of nationality or gender, including both new graduates and mid-career hires.

While there is a widespread preconception that employees who work in long-term membership-based employment environments have a strong sense of belonging and loyalty to the company, this is not always the case. In opinion surveys of Hitachi employees, the engagement scores for Japanese employees are lower than those for overseas employees of group companies.

The main problem I see is a lack of individual independence (or autonomy). Rather than an attitude of wanting to advance one’s own career, there is a strong tendency to leave that career in the hands of the company. I suspect that this lack of a spirit of self-reliance is having an impacting on engagement and productivity. Overseas employees typically have a strong sense of their career being something that they build for themselves, with management-level employees in particular actively seeking out work that is not on their job list in order to expand their scope of authority. The idea that job-based employment means being restricted to designated work only is another misconception.

The true nature of job-based employment is about asking what employees want to do with their lives, what they need to make this possible, and what capabilities and skills employees should be developing so that, by achieving clarity, they are able to take practical action. The employee’s life is their own and it is up to them to advance their own career and take advantage of their opportunities. The company, for its part, can get fully behind this by actively investing in an employee’s progress.

Clearly, we do not want to extinguish the culture of valuing employees that Japanese companies have built up. However, in my view, this clearly does not mean protecting everyone out of a sense of comradeship, but rather providing the unerring support to foster employees so that they can live independent lives. The organization itself becomes stronger when all employees are able to make use of their strengths, and this is a source of benefit for both employer and employee.

It was thanks to having spent such a long time working on reforms like this that Hitachi was successfully able to introduce telework on a large scale during the current pandemic. However, if employees are to be active globally while working together in a primarily virtual environment, then measures to complement this style of working are a matter of urgency. Meanwhile, Hitachi recently established Hitachi ABB Power Grids Ltd., having acquired the grid business of the Swiss-Swedish electrical engineering company ABB. As with human capital management systems, there is also an urgent need for the reform of training systems if operations are to be genuinely global. In order to expand its Social Innovation Business, Hitachi intends to further develop its training and management practices for the employees who are the driving force behind this growth.