Formulation of Activity Patterns for Social Implementation of Cyber-systems

Highlight

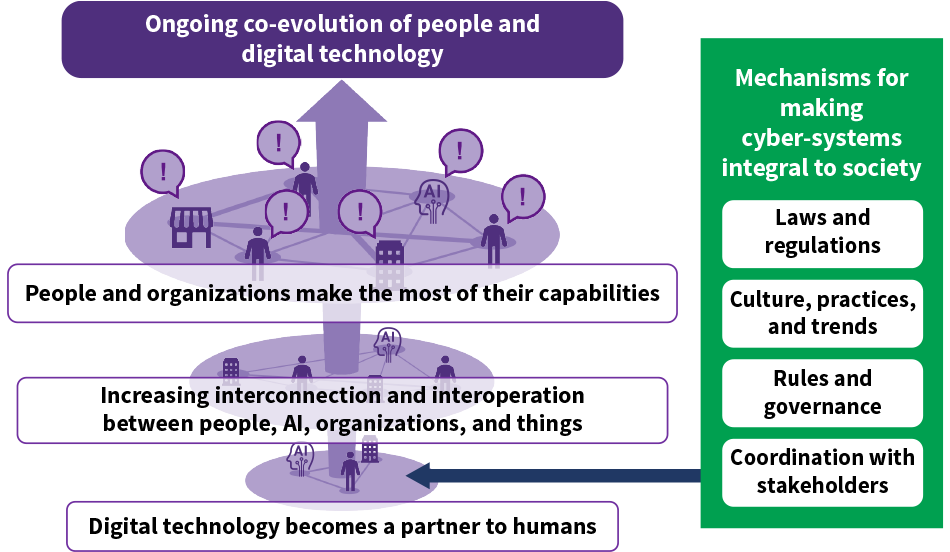

The co-evolution of people and digital technology will accelerate as cyber-systems become integral to people’s lives, as exemplified by Web 3.0, the metaverse, and generative AI. However, if society is to realize this prospect of a desirable future, one in which people and organizations can make the most of their capabilities, it will require not only the delivery of technologies, but also mechanisms for making cyber-systems an integral part of society.

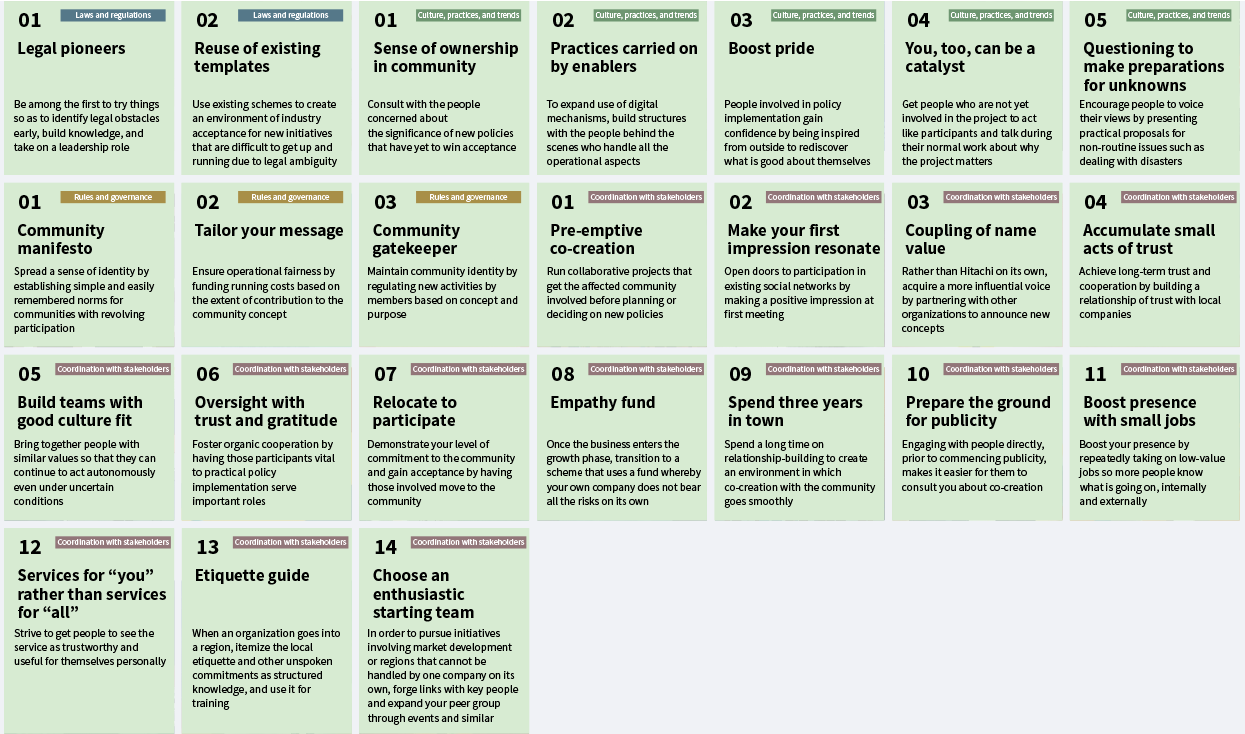

Through a review of 21 co-creation projects undertaken with both internal and external partners, Hitachi has identified four factors that are crucial to the social implementation of cyber-systems, namely laws and regulations; culture, practices, and trends; rules and governance; and coordination with stakeholders. Further work entailed reviewing the characteristic activities undertaken in past projects in the light of these considerations and using this to create a knowledge-base of the associated activity patterns that occur during social implementation.

This paper introduces the details of these efforts and describes future prospects for the continuous accumulation of knowledge and the development of systems for its utilization.

1. Introduction

Uncertainty is becoming ever more prevalent as distribution networks grow and digital technologies become increasingly integral to people’s lives. This situation has come about through the strengthening of links between people around the world, such that people’s autonomous actions now have consequences that extend more quickly and more widely than anyone ever imagined. The COVID-19 pandemic has likewise had a major impact on society. One such impact that warrants particular attention is how the use of digital technology expanded during those times when people’s movements were being constrained to prevent the spread of infection, boosting public familiarity with cyber-systems such as Web 3.0, the metaverse, and generative artificial intelligence (AI).

This article defines cyber-systems as systems that, through the interconnection of people, organizations, and things that were not previously interconnected, enable people and organizations to make the most of their capabilities, transform how people and organizations relate to one another, and expand the possibilities of society.

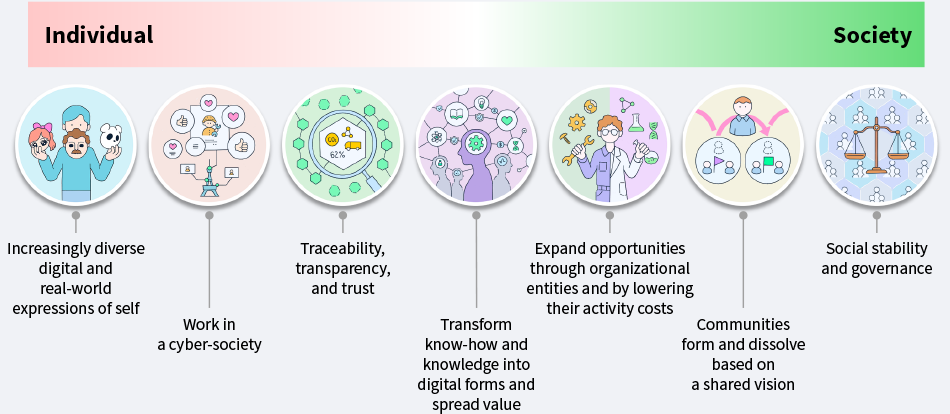

To depict what society might look like around 2030 when cyber-systems have become ubiquitous, Figure 1 shows seven considerations that were derived from indicators of daily life. Cyber-systems will further accelerate globalization, transforming organizations and how the world communicates and shares knowledge. The consequences of this will extend into areas of life that are currently taken for granted, including the ways in which people work and earn a living, their ethical values, and the design of their lives.

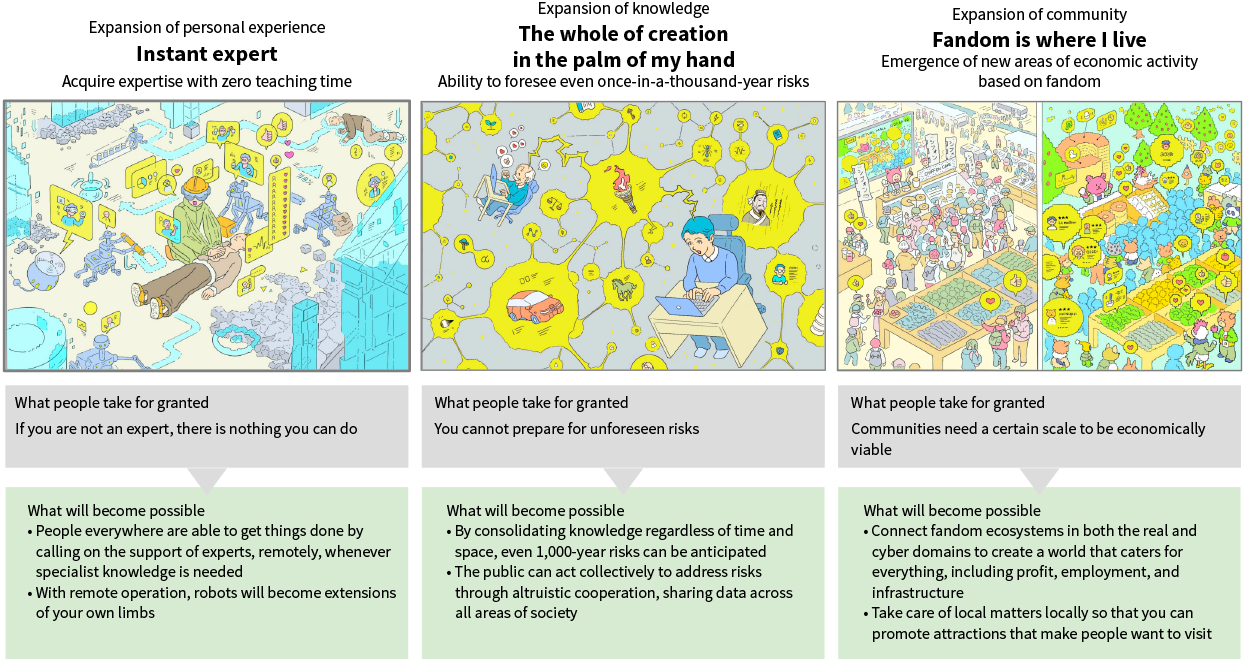

Figure 2, meanwhile, presents specific examples highlighting anticipated changes that arise out of the seven considerations depicted in Figure 1. The “instant expert” example expands on personal experience by giving people the ability to acquire and put to practical use the specialist knowledge and experience they need in specific circumstances, and to do so quickly and regardless of time or place. “The whole of creation in the palm of my hand” is an example of the expansion of knowledge. While people are still the ones who decide their own actions, here they have gained the ability to make better decisions even in exceptional cases through awareness of what is happening in the wider society to which they belong. Through this process, a diverse variety of sensors and the prediction functions that make use of them will fulfill the role of expanding on human wisdom. “Fandom is where I live” is an example of the expansion of community. This depicts a scenario in which fandom activities directed at a wide variety of interests can build communities in a way that energizes the real economy, one that takes place against a backdrop of diverse relationships, not only those between people.

Figure 1—How Living in a Cyber-society around 2030 Will Change Private and Public Life Hitachi has identified seven considerations relating to how to distinguish between different types of people, concepts for how income is earned (work), the purpose of organizational entities such as companies and communities, and the handling of knowledge as a source of value.

Hitachi has identified seven considerations relating to how to distinguish between different types of people, concepts for how income is earned (work), the purpose of organizational entities such as companies and communities, and the handling of knowledge as a source of value.

Figure 2—Examples of How Cyber Practices Can Expand Possibilities * Cultures and domains built by enthusiastic fans with a wide range of different interestsThe images represent anticipated changes that arise out of the seven considerations. For the three examples of “expansion of personal experience,” “expansion of knowledge,” and “expansion of community,” the images indicate the direction of future change by showing what people currently take for granted and what will become possible in the future.

* Cultures and domains built by enthusiastic fans with a wide range of different interestsThe images represent anticipated changes that arise out of the seven considerations. For the three examples of “expansion of personal experience,” “expansion of knowledge,” and “expansion of community,” the images indicate the direction of future change by showing what people currently take for granted and what will become possible in the future.

2. Co-evolution of People and Digital Technology

The above three examples show how capabilities can be expanded. They paint a picture of the world in a few years’ time in which digital technologies are continuing to change. These changes in turn will give rise to changes in the values, thinking, and activities of the people who use digital technology. A society in which cyber-systems are ubiquitous is a society in a process of never-ending change, one in which people and digital technologies influence one another and evolve together. Figure 3 shows a cross-section of a society that is changing over time along the path set by this co-evolution.

The first stage is the current situation where, with the emergence of generative AI, digital technology starts to be used routinely as a partner to humans, becoming something more than just a convenient tool. The next stage is one of increasing interconnection and interoperation between people, AI, organizations, and things. This is a stage in which communities and companies make ongoing progress, as measured by performance indicators such as economic efficiency, with inter-AI coordination, data from diverse sensors, and analysis techniques becoming more commonplace. The final stage is when people and organizations are able to make the most of their capabilities and are able not only to enjoy the benefits of digital technologies, but also to achieve a higher level of wellbeing.

Figure 3—Possible Future Path for Creating a Society People Want AI: artificial intelligenceAs interactions increase between people and digital technologies, it is anticipated that they will evolve together. The goal is to create a society in which, when this happens, people and the organizations to which they belong can make the most of their capabilities.

AI: artificial intelligenceAs interactions increase between people and digital technologies, it is anticipated that they will evolve together. The goal is to create a society in which, when this happens, people and the organizations to which they belong can make the most of their capabilities.

What needs to be done if society is to become a place where people and organizations make the most of their capabilities? In his book, “Realizing the Future: Four Principles for Transforming Society through Technology,”(1) Takaaki Umada, Director of FoundX* at the University of Tokyo, wrote, “What is lacking from Japan’s society is not innovation in technology but in how to go about changing society.” Also, “When considering how to establish a technology in society, we have reached the point where we need to shift our thinking away from introducing it into society and towards introducing it as part of society” (emphasis from original text).

Regional reforms in Europe offer examples of this approach of introducing technology as part of society. In the Smart Citizen Project(3) that emerged from the work of Fab Lab Barcelona(2), for example, sensors were installed to allow residents to take their own air quality measurements. Moreover, instructions on how to put the sensors together were made public through the Making Sense Project(4). Likewise, the Street Moves Project(6) led by VINNOVA (the Swedish Governmental Agency for Innovation Systems)(5) had residents of Stockholm, including children, design local roads for themselves.

To achieve this introduction of technology as part of society, it is important to review the key points and actions to take during the transition from stage 1 to stage 2 in Figure 3, especially regarding interaction with the public and other stakeholders, and to identify these as mechanisms for implementing cyber-systems in society. One such mechanism that Hitachi has constructed is a set of “activity patterns for social implementation.” These are described in detail below.

- *

- A free program for teams made up of graduates and researchers from the faculties and graduate schools of the University of Tokyo.

3. Activity Patterns for Social Implementation

Activity patterns for social implementation include both practical examples and collected knowledge of actions taken to resolve the problems that arise when establishing cyber-systems as part of society, especially those problems of a non-technological nature. In addition to use as a reference when innovators engaged in the social implementation of technology are uncertain about how to proceed, the goal is also to facilitate the ongoing collection of knowledge by accumulating the expertise acquired from practical experience in a standardized format. This section describes the four factors considered when formulating the patterns along with the patterns themselves.

3.1 Four Considerations Identified from Review of Past Projects

To formulate the activity patterns for social implementation, interviews were held with people who worked on 15 multi-stakeholder co-creation projects in which Hitachi had an involvement and desktop research was conducted that looked at six projects from outside Hitachi. The results indicate that, in addition to having a strategy for legal aspects and regulatory agencies, the adoption from an early stage of an approach that addresses user acceptance and other social norms is an important factor in achieving a successful social implementation. It was also noted, however, that not only does it take time for social norms to change, in many cases the views of communities or the industry as a whole bear more heavily on such changes than do those of individual organizations.

From these observations it was concluded that, in addition to the two considerations that bear on social norms, namely “laws and regulations” and “culture, practices, and trends,” “coordination with stakeholders” and “rules and governance” are also needed to strengthen engagement with communities.

3.2 Identified Patterns

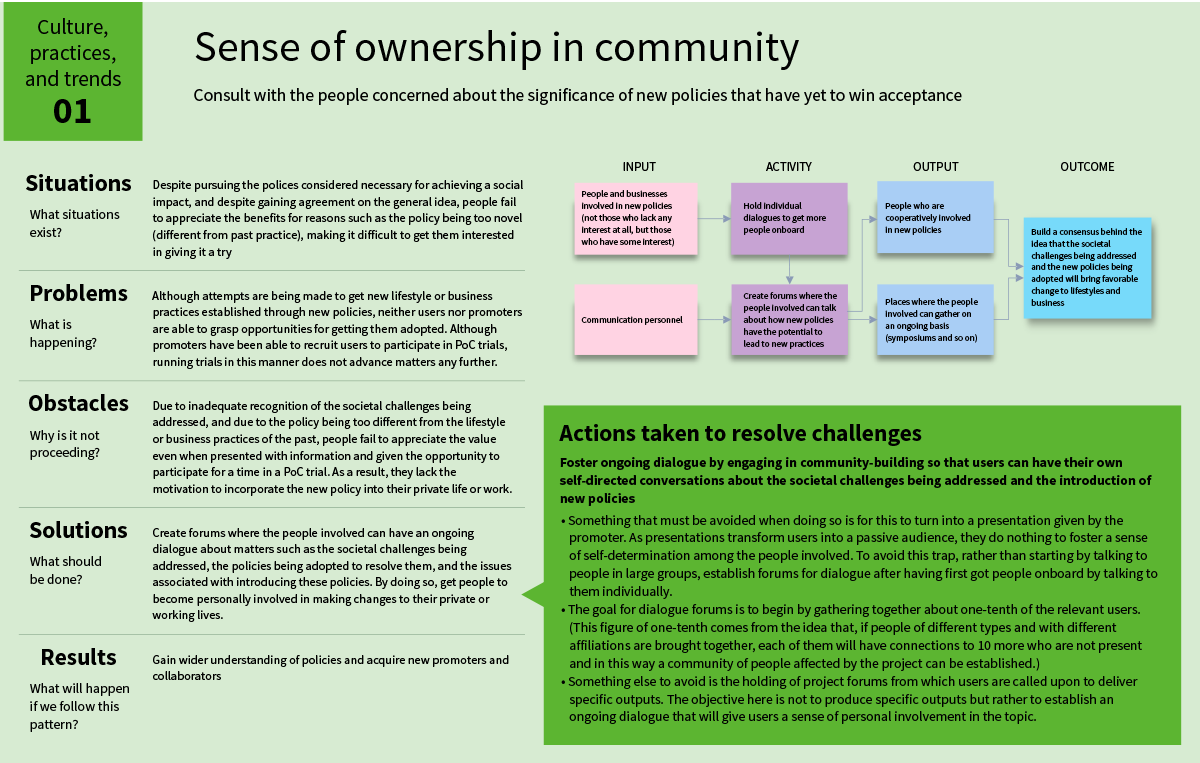

The activities characteristic of the past projects were collated on the basis of the above four considerations and established as a knowledge-base representing the activity patterns for social implementation. Figure 4 lists these patterns and Figure 5 shows examples.

The activity patterns for social implementation were expressed using a pattern language. A pattern language is a form of knowledge representation proposed by Christopher Alexander for resident participation in urban development(7). As the work being described here deals with a human activity (the social implementation of technology) rather than domain classification, Professor Takashi Iba of the Faculty of Policy Management at Keio University used Alexander’s pattern language and adopted a notation devised for representing aspects of human activity(8). This works by separately specifying situations, problems, obstacles, solutions, actions for putting solutions into practice, and results, with titles assigned to symbolize their features.

The patterns are based on activities that occurred in one or more past projects and are expressed in a generalized form to make them easy for innovators to apply to their own projects. Unfortunately, this generalized notation does not give a good sense of what they look like in practice. Accordingly, Hitachi has provided reference information for each pattern that uses a standard format to present relevant situations, problems, actions for putting solutions into practice, and other material relating to the past projects on which the patterns are based.

4. Conclusions

The work described in this article used past projects at Hitachi and elsewhere to establish activity patterns for social implementation based on the idea that mechanisms for making cyber-systems an integral part of society will be vital if digital technology is to be used to create societies in which people and organizations can make the most of their capabilities.

The patterns were shared with innovators at Hitachi who gave positive feedback in interviews, commenting that they were not weighed down with superfluous material and should prove useful. The feedback also highlighted issues regarding the breadth versus depth of the knowledge, with people asking for a greater depth of information and for patterns that closely match the situations they are currently facing. Future plans include system implementation and studies into how to sustain the ongoing collection of more in-depth knowledge.

REFERENCES

- 1)

- Takaaki Umada “Realizing the Future: Four Principles for Transforming Society through Technology,” Eiji Press Inc., pp. 42-44 (Jan. 2021)

- 2)

- Fab Lab Barcelona

- 3)

- Smart Citizen

- 4)

- Making Sense

- 5)

- VINNOVA

- 6)

- Street Moves

- 7)

- C. Alexander, et. al., “A Pattern Language : Towns, Buildings, Construction,” Oxford University Press (1977)

- 8)

- T. Tba, “Pattern Languages: Languages for Creating Imaginary Futures,” Keio University Press Inc. (Oct. 2013)